Several times during our years of teaching Systems Leadership we have explored the role of higher education and the impact of universities in their communities, their regions, and across the world. In one session with the former President of The Ohio State University, my co-teacher, Jeff Immelt, called education “the Great Equalizer” for individuals. His assertion was not only about students gaining knowledge and capabilities while in school, but also their acquiring access to resources and networks that otherwise might not be available.

During the pandemic some (including me) thought that remote teaching would revolutionize education. Instead of only teaching those students in front of us in a classroom, we would reach people all over the world using interactive technology. This capability could reinforce the mission of many academic institutions: the discovery of new knowledge via research, and the dissemination of this information into society via teaching.

Alas, remote teaching has not had the transformational impact on universities and society as hoped. While some online programs have become more available to a broader audience of students, the teaching activities of most schools have returned to focus on in-person instruction. Perhaps this should have been expected given that the pandemic Zoom experience was not only not as good as being in the classroom, but the memories of those times are not happy for either students or instructors.

Why go back to something that wasn’t particularly pleasant or rewarding?

A Blank Sheet in Morocco

Last month I spent a week at the University Mohammed VI Polytechnic (UM6P) in Benguerir, Morocco. The institution was set up in 2013 as a private research university to increase technical competency and development in the country and region. The campus now has over 4,500 students who come from all over the world and has quickly become a top-rated institution in Africa.

I was greatly impressed not only with the quality of the facilities (the architecture reminded me universities you would find in the American Southwest), but also the energy of the faculty, administration, and students. The technical capabilities and resources for the education process were hugely impressive for a campus that is barely a decade old. Perhaps more exciting was the enthusiasm of the young people — their desire to learn, to contribute new ideas, and to participate in the advancement of the country and economy. The environment was as lively and dynamic as any academic location I have witnessed.

Reinvention in Saudi Arabia

After departing Morocco I arrived in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, a city and country I have seen change greatly since my first visit seven years ago. Part of what struck me when I arrived this time was how much more advanced Saudi Arabia felt than Morocco. At first, I wondered why the spread appeared so great. Both countries have similar populations (36-38 million people), and Morocco’s historical proximity and ties to Europe should create competitive advantage given the large diaspora of Moroccan citizens in France and across the European continent.

In a blinding glimpse of the obvious, I realized that the GDP of Saudi is 10x greater than Morocco’s, and the wealth created from the nation’s natural resources has given it a huge advantage as it modernizes its economy and society for the 21st Century. The creation of King Abdullah University in 1967, and more recently the founding of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in 2009, has enabled the education and development of Saudi citizenry not only to support the energy sector, but new areas such as computer science and healthcare. Over one million citizens attend universities in Saudi, up from fewer than 10,000 in 1970, and the government provides funding for students to attend universities outside of Saudi in Europe, North America, and elsewhere.

My visit to the Kingdom involved working with the next generation of healthcare leaders in the country, engaging on their management and leadership skills as the country modernizes and improves its healthcare system. The commitment of all the parties involved — the government and of the doctors and administrators I was with — was striking in its earnestness and conviction.

And Finally, Europe

As my travel continued, I next went to Switzerland and visited IMD (International Institute of Management Development) in Lausanne. While the institution is a relatively new university by European standards (created in 1990 from a combination of two schools founded earlier in the 20th century) the international faculty and curriculum felt closer to what I experience at Stanford — a traditional Western education applied to general business development and management.

I felt at home talking with the faculty at IMD — their experiences and perspectives on strategy, finance, product management, and entrepreneurship were familiar. The faculty’s willingness to compare notes and challenge ideas was very comfortable. And I enjoyed seeing a different venue and culture than where I have spent most of my time in front of a classroom for the last 21 years.

Not in Sync with the People They Serve

As I reflected on these three educational visits, I became even more convinced of my belief that higher education in the United States is confronting an existential crisis. As is widely known, there is a distinct lack of trust in academic institutions:

Rising college debt, research misconduct, tensions over conflicts in the Middle East, and the sense that universities have become inbred and intolerant is affecting alumni donations and perceptions of the value of a college education.

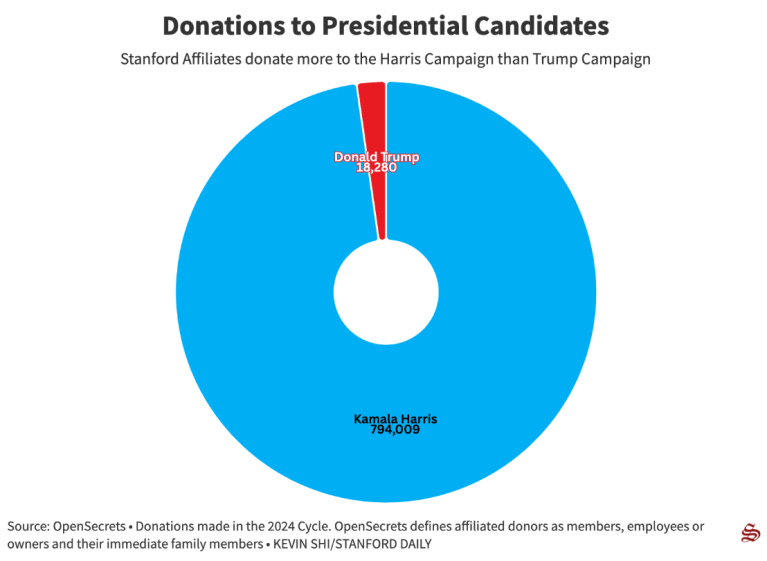

On this last item, there is a very real monoculture that has taken over most parts of American academia. As an example, Stanford resides in a country that for the last 2+ decades has been divided roughly 50/50 politically. Yet, The Stanford Daily reported that over 96% of political contributions of Stanford-affiliated donations were made to one presidential candidate in this recent election cycle:

And this has increased substantively over the last eight years.

My point is not a political one; rather, that institutions of higher learning in the United States today do not accurately reflect the society and communities in which they exist. Despite efforts to have broader representation of gender and race, culturally these institutions are substantively unrepresentative of society.

Higher education has become an echo-chamber at the extreme, which is contributing to/causing the lack of trust in broader society to these institutions.

When one is living in the middle of this volatility, it is reasonable to wonder if education’s best days are behind it. What has for some (including me) been a professional calling can feel like our campuses are decaying due to a lack of leadership, absent understanding of purpose, convoluted intellectual honesty (at best), and downright missing moral clarity.

In some ways, if higher education’s role has become largely to help undergraduates and graduate students find jobs to justify the enormous financial investment needed to get a degree, it’s no surprise that universities have become paragons of virtue signaling in order to help justify their existence.

In the end, if universities are evaluated largely as trade schools, and the ultimate value of the degree has devolved into certification for job prospects, the false creation of “noble goals” would be a logical strategy to show value beyond the solely economic transactional nature between institution and student in a hollow attempt to harken back to these campuses’ original missions.

And Back to Benguerir…

My mind keeps drifting back to UM6P. I think of my former Stanford student who returned home to Morocco so that he could take a job on campus that pays him 20% of what he would make in the San Francisco Bay Area. I saw firsthand his commitment to growing the scientific and technical ecosystem in his homeland.

I observed a research institution that has also added a program to teach software coding in which faculty don’t exist, the curriculum is developed around the world by clusters of individuals, and students are evaluated by their peers for their programming competencies. If necessity is the mother of invention, UM6P is leveraging the support they receive from the government, local industry, and the Moroccan diaspora to improve the well-being of the community, the city, and the country.

I also think of the healthcare professionals in Riyadh who want to grow their managerial skills as they evolve from solely practicing medicine to helping build systems that can scale wellness throughout their country.

And I wonder how I can bottle what I experienced abroad and bring it back home to higher education in the United States, which, according to the data, has so clearly lost its way and its connection with society.

How can education be the Great Equalizer if our educational institutions are out of touch with those we serve?