I’m at the stage of life where I am checking items off my bucket list. One thing that I desperately wanted to do before leaving this world was see the animals in Africa. Last month Debbie and I spent 11 days in Tanzania and Kenya experiencing the dynamics of the continent – from the vibrant nature of the Serengeti to the vastness and elegance of the Maasai Mara.

On our trip we met several newlyweds also taking in the sights of these natural wonders. At dinner one evening we chatted with a young couple from Atlanta and compared notes about taking photos of wildlife. Over the trip I snapped over 10,000 pictures, and I thoroughly enjoyed the ability to use a DSLR camera to capture so many interesting moments.

As the four of us were eating our meals, the new groom marveled at the ability of AI to combine parts of multiple rapidly taken images to put together the best possible photo combined of components of each picture. I contemplated this scenario, and then asked,

“If the purpose of taking pictures is to capture moments so that they can be remembered, such an amalgamation of AI would not be real. You didn’t really see what the AI would construct. It would be a fake memory and a fake image.”

He replied, “But how is that different than things like Google’s Best Take feature, which allows people to put together a new picture that can fix situations where someone was blinking their eyes when you captured a photo? With Google’s technology, you can easily solve that.”

It was a good question to which I did not have a ready answer.

“But the AI picture is still a fake. It’s not real,” I posited.

My wife then pointed out that these creations are the opposite of deepfakes – they are “shallow-fakes” or “nano-fakes.”

I pondered that if I put together an AI-edited set of photos from our trip, these pictures would not be actual representations of what we witnessed. When we looked at the photos later, would they help us remember what we saw, or would they create a fantasy that was never actually there?

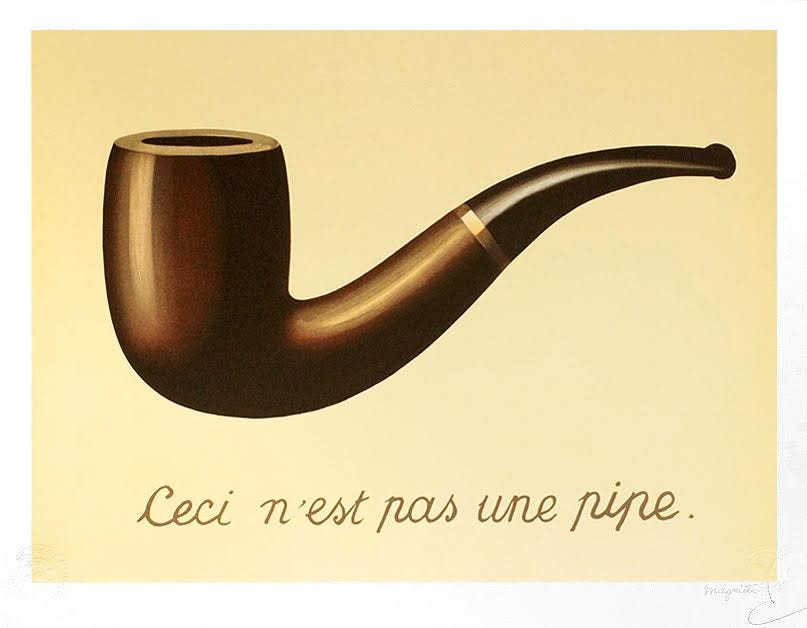

This Is Not a Pipe

As I considered this paradox my mind drifted to the Magritte painting entitled The Treachery of Images:

When the artist wrote, “Ceci n'est pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”) he was stating that his painting was not a pipe, but merely a representation of a pipe. The pipe he created could not be smoked nor stuffed – it was simply an image.

In modern times we confront a new conundrum – not only are items in images not the actual items (as Magritte highlighted), but now we can create images from combinations of pictures that express moments that never existed. These constructs come from multiple photos and create something that never happened. And with AI this goes well beyond “Photoshopping” an image for minor image correction — we can do so much more than just touch-up a picture. We can create entirely new things that look so real we often cannot tell that they are fake.

But does this matter? How bad is it to remove someone’s blinking eyes out of a photo, and where does it cross the line into something unacceptable or upsetting? Is the problem when people try to represent something that didn’t happen, such as creating an image or video of a person doing something that never really took place? Is the issue when people try to fool others into believing something that is not real? Is it the intent of creating something fake that is the vexing issue, or is it the mere creation of a false reality that never existed and passing it off as reality that becomes problematic?

Which brings us to a fundamental issue confronting society — the ability to tell the difference between what is real and what isn’t.

Reality and Leadership

Steve Jobs was celebrated for his having a “reality distortion field” – he would assert that something was true (even if it wasn’t) to rally support and engagement of others to bring his vision into existence. We lionize entrepreneurs and leaders who can “see around corners” and put “dents in the universe” to make new things happen – but the initial ideas of these people do not exist in reality – until they do.

If they ever do.

Some might refer to this trait as a leader having a “vision of the future” – to see things that others do not. We celebrate those who see that which does not exist today and then bring it into the world through invention and hard work.

Perhaps the challenge is that a reality distortion field is ok when describing potential futures, but it becomes problematic when people are rewriting (or recreating) a past when that past never happened.

Building Trust in an AI and Data-Driven World

Building trust is much more complicated than it used to be, and it is so much more important.

When we read about the decline of trust in institutions — political, business, and education — much of it is driven by our not believing what we see and hear, and the sense that those in positions of power are acting in their interests versus our own. When we studied companies combining digital and physical solutions in The Industrialist’s Dilemma at Stanford, we explored how the financial services firm Charles Schwab has a tremendous amount of data, but that their “North Star” on using this data is managed by the question, “What would our clients want us to do with this information?” The company’s mantra for their activities is to take actions “Through clients’ eyes.”

One can juxtapose this sentiment with how most people look at Meta, OpenAI, banks, or many other large organizations (including governments). Do these institutions use our data for what is in our interest or what is in their interest? Do they act and behave in a way that prioritizes what we want as customers, individuals, or citizens, or are they primarily driven by their own self-interests — and we are simply tools for their achieving their goals — financial, power, or otherwise.

Ironically, this creates a huge opportunity for leaders in today’s world. In a landscape of individuals and organizations that seem to act in a way that makes them unworthy of our trust, the ability for leaders to guide and connect by prioritizing those that are served (e.g. customers) creates the chance to stand apart from the competition. This is not to say that leaders must choose between being ambitious and being altruistic in their behaviors. Rather, it is about finding a balance between both objectives.

In a world where trust is increasingly difficult to hold, the ability to establish and maintain trust is a source of tremendous competitive advantage in the future. In our course on Systems Leadership we have studied a number of men and women who model this behavior while balancing the enormous cross-pressures of today’s challenges. The leaders we have hosted are ambitious and successful by any measure, and many are not widely prominent on social media or in the press. Each works hard to prioritize building trust with those they serve — customers, employees, suppliers, and other fellow travelers in their ecosystems.

While none of these people are perfect — they make mistakes which are often in the public eye — they are all very purposeful in understanding the challenges of today’s world and how they must lead their teams with trust in these volatile times.

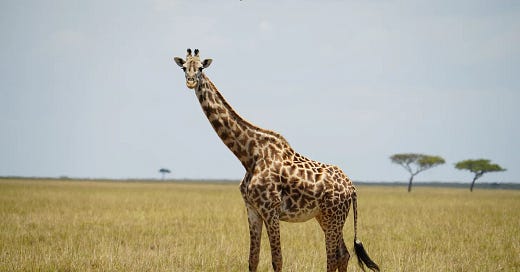

Ceci n'est pas une Girafe

As Magritte would surely agree, this is not a giraffe – it is simply a picture of a giraffe.

Just under a month ago on a random afternoon in Kenya, this giraffe stared at me without flinching for about 60 seconds. Who I was, and what I was, mattered little to this animal beyond our passing interaction. The machinations of our human world were irrelevant to this creature. Wars, elections, artificial intelligence — none of these things were a part of its existence.

Eventually, the giraffe ambled on its way to the next tree where it gathered with its family without any need to think about deepfakes, trusted institutions, or putting a dent in the universe.

The giraffe existed in its own perfection, captured in this unmodified image.

The photo is my unedited memory of the moment. Maybe I could have made a slightly better image with the help of AI, but this happened exactly as it appears.

And it was amazing.